Far Right Surge Casts A Shadow Over Women's Rights Progress in Spain

Recent feminist advances echo those of the Republic. Would a future right-wing government turn the clock back on women's rights?

This edition is authored by Verónica Lawson Vilches, a Spanish-American historian, copywriter and communications professional who works with impact driven founders and organizations. You can learn more about her work on The Word On Record and follow her on LinkedIn.

It is impossible to imagine a woman in modern times who, as a basic principle of individuality, does not aspire to freedom.

- Clara Campoamor, Spanish feminist lawyer and member of parliament (1931-1933)

As Spain prepares for the upcoming elections on July 23rd, the rise of the right wing over the past decade is undeniable.

Spain’s Vox party mirrors other populist and far-right parties across Europe, such as the National Rally in France —led by Marine Le Pen—and Giorgia Meloni’s Brothers of Italy. Worldwide, headlines suggest that Vox could become a junior partner of a right-wing coalition.

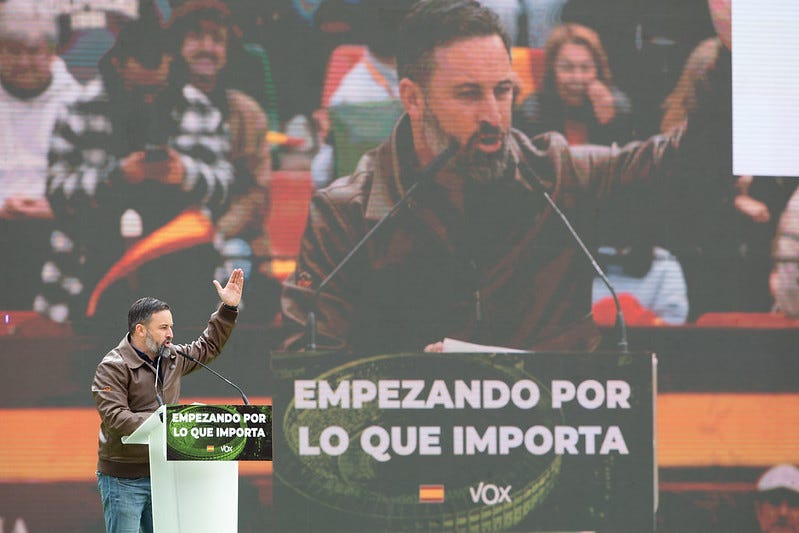

Founded in 2013, Vox takes its name from the Latin word for ‘voice’. In 2018, the party made surprising gains by winning 12 seats in Andalusia’s regional elections, marking the first time since the dictatorship of Francisco Franco (which ended in 1975 at his death) that a far-right party had obtained representation in the Spanish regional parliament. Vox’s leader, Santiago Abascal, echoed the rhetoric of former US President Trump, vowing to “make Spain great again” and give a voice to those who have been forgotten. The question is: who exactly?

Machismo is an aspect of Spain’s identity that it has been trying to lose. Less than 50 years have passed since Spain was under a regime where women were denied the right to vote, file for divorce, work, have access to a bank account, or receive adequate education. During Franco’s regime, women were expected to conform to the rigid role of being perfect wives and mothers, as prescribed in books and pamphlets like Cómo ser una buena esposa (How to Be a Good Wife).

Although Franco’s death in 1975 marked the end of fascism in Spain, its transition to democracy is often hailed as “almost perfect”. It has served as a model for other countries on their own paths to becoming democratic countries. Yet shedding the deeply ingrained ideologies of the past has proven challenging. Spain’s political landscape has alternated between the Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party (PSOE) and the moderate-right People’s Party (PP). Former Prime Minister Jose Luis Zapatero, who served from 2004-2011, proclaimed himself a feminist and played a pivotal role in passing a landmark bill on gender violence. His law covered everything from prevention and care for victims to the criminalization of the crimes committed by the aggressors. Additionally, it established that this form of violence is structural and specific against women.

Despite these political advances, Vox’s growth and its opposition to legal changes and feminist victories mirror Spain’s own complex history. Feminist groups have continued working to grant women more rights.

Yet the resurgence of the right wing could pose a threat to their progress.

The Second Republic’s Feminist Legacy

The Franco dictatorship was a major setback for women's rights in Spain and curtailed important previous advances during the period of the Second Republic. Lasting only from 1931-1939, the Second Republic was a transformative time in Spanish history. It emerged as a response to the long-standing monarchy and aimed to establish a democratic and egalitarian society.

During this period, Spanish women challenged the deeply ingrained gender norms that defined their roles and identities. The feminist discourse of the time was shaped by the societal and cultural context, characterized by a conservative Catholic influence and a traditional patriarchal structure.

On November 19th, 1933, women were allowed to vote in the national elections for the first time. The right was earned only two years prior when a measure was adopted on October 1st, 1931, granting them the constitutional right to do so.

By enabling a right to their voice, changes to the educational system and professional fields allowed more opportunities for women. By providing them with the tools to achieve economic independence and social mobility, women were able to challenge traditional gender roles and contribute to sectors such as law, medicine, and journalism. Prominent figures of that time period have left a mark on history that we still note today. Josefina Carabias was the first woman journalist of Spain, and her daughter, Mercedes Rico, was one of the first women diplomats after Franco lifted the ban on women in the position.

In the early and mid-1930s, women actively participated in labor movements, advocating for fair wages and improved working conditions. In rural parts of the country, agrarian women organized themselves to address issues such as land reform, access to education, and healthcare. Not only were women fighting for their rights, but also making advances on class-based exploitation.

Similarly, Spain saw progress in terms of divorce legislation. In 1932, a law was passed that allowed for civil divorce, providing women the opportunity to dissolve unhappy or abusive marriages. It was a significant departure from the prevailing social norms and religious influences that had stigmatized divorce.

In terms of reproductive rights, the Second Republic took notable steps towards decriminalizing abortion. In 1936, abortion was legalized in Catalonia and in the next year it was legalized nationally. It was the most advanced law on abortion for its time in Europe, but repealed after Franco won the Spanish Civil War.

These changes were notable in the European context at the time, as Spain was among the first countries to grant such extensive rights to women. It reflected the efforts of progressive thinkers who wanted to improve the status of women in Spain. This period represented important steps towards achieving gender equality and providing women with the legal and social frameworks necessary to exercise agency over their own lives. If this course would have continued, Spain could have become one of the leaders in gender equality.

Unfortunately, these reforms were not universally embraced. Conservative and religious factions within Spanish society vehemently opposed these changes and viewed them as a threat to traditional values and institutions. When Francisco Franco and the right wing won the Spanish Civil War in 1939, these liberal reforms were repealed and it wasn’t until Franco’s death in 1975 that they would be seriously revisited. Women’s rights were severely curtailed for 36 years. During the Francoist regime, under civil law, unmarried and married women were subjected to the guardianship of their fathers, brothers and husbands, limiting their autonomy.

At the end of the Franco era, the advancements that had been made by the Second Republic were revisited and were an inspiration and the foundation for Spanish feminists, who built on the ideas that had been lost to fascism in Spain.

Progressive strides and lingering challenges

By the end of the Franco regime, many reforms to women’s rights were being made. Franco’s reconsideration of social laws could be attributed to many factors, most likely driven by the aim to integrate Spain into the international community and with the tourism boom experienced in the 1960s. Internally, there were also various demands for equality and a push for social progress.

In 1975, the permiso marital, which required married women to seek their husband’s permission for various legal matters, was abolished. The 1978 Spanish constitution established equality under the law for men and women.

By the early 1980s, Spain was in full swing at retracting the laws that constricted women, granting them full civil rights, legalizing divorce and decriminalizing contraception. With the creation of the Instituto de la Mujer (Women’s Institute), it provided institutional support for gender equality initiatives. By 2004, Spain passed the Gender Violence Law, providing comprehensive measures to address and prevent violence against women and being considered a pioneer country on the issue. A radical change to its recent history. Passing a groundbreaking law compared to European counterparts and worldwide was an echo of Spain’s past during the Second Republic.

Not surprisingly, progressive legislation championed by the government has been met with skepticism from the right wing.

Irene Montero, the Minister of Equality in Pedro Sánchez’s government, has been defending forward-thinking legislation, at times setting Spain apart from its European counterparts. In early 2023, Spain was the first European country to pass a paid ‘menstrual leave’ law. Viewed as an advancement by some, it still sparked concern on whether it will help or hinder women in the workforce. This bill was part of a broader package on sexual reproductive rights, including the right to access abortion and change gender on identification cards for individuals 16 and over.

Despite significant advancements, Spain has seen persistent violence and the effects of the macho attitude of its past. Just a few years ago, Spanish law defined “sexual aggression” as requiring the use of violence and intimidation. This sparked an outlash when an 18 year-old was gang raped that year by five men, known as La Manada (the wolf-pack) at the bull-running festival in Pamplona. Two of the men had filmed the assault as the woman was shown silent and passive - a fact that the judge interpreted as consent. The aggressors were initially convicted of “sexual abuse”, sparking huge protests nationwide. By 2019, the Supreme Court overruled the verdict and increased their sentences from nine years to 15 years each. Sánchez, a self-described feminist, promised to introduce a law on consent that would remove any kind of ambiguity in rape cases. Just under a year ago, Spain passed the “Only yes means yes” law.

Only 12 of 31 European countries have changed their legal definitions of rape to emphasize clear consent, including Belgium, Denmark and Sweden.

“No woman will ever have to prove that violence or intimidation was involved in order for it to be considered a sexual assault,” proclaimed Montero.

Sadly, the law contained a loophole that allowed more than 700 sexual offenders to reduce their prison terms, an irony not lost on the right wing, who make this one of their key points of contention against the left-wing government during the campaign.

The potential impact of the right wing in Spain

Similar to far-right movements in Italy, Hungary, France and its own past, Vox embraces conservative attitudes towards women and holds on to the traditional concept of family (with a father, mother and children).

When it comes to gender violence, Vox argues that “violence has no gender or labels”. In Andalucia, where Vox gained 12 seats in 2018, funding for 78 organizations working to eradicate gender-based violence, was cut overnight in 2019. That same year, Vox refused to sign a joint declaration across all parties condemning violence against women, marking the first time since 2004 that such a joint statement could not be issued. Abascal, in an interview in 2020, stated that 70% of gang rapes in Spain are committed by foreigners. In Valencia, where Vox shares regional power with PP, the definition of domestic violence was changed to ‘intrafamilial’ violence.

On July 7th, Vox proposed abolishing the current laws allowing abortion, and would increase parental control on sex education to allow them to veto what they don't deem appropriate education.

A telling indication of Vox’s views on women, immigrants, and the LGBTQ+ communities is evident in the billboard in Madrid that depicted the flags and symbols of these movements being discarded into a bin.

The potential victory of the right wing in the upcoming July 23rd elections and the repeal of feminist advancements that would be made in Spain is a deeply concerning prospect for women’s rights. Spain has made remarkable progress in dismantling the patriarchal structures of its past, expanding women’s rights and trying to foster a more inclusive society. Perfectly? No. For example, what could have been a momentous win for survivors of sexual assault in Spain was diminished by Montero’s law’s loophole.

Yet, the rise of the far right, not just in Spain, but in Europe and the U.S., threatens to undo hard-fought gains for minorities and undermine the fundamental principles of gender equality. The repeal of such social advancements would erase the strides in areas such as reproductive rights, gender-based violence prevention, and workplace equality. This is an alarming prospect for many.

The prospect of regressing back to a time when women’s voices were silenced and their rights were curtailed is a haunting reminder of the battles from Spain’s past.